United States > Migration > Trails and Roads - ACS E

advertisement

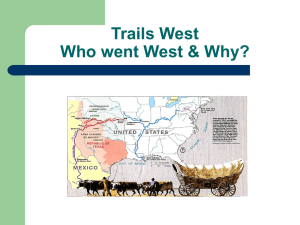

LEWIS AND CLARK EXPEDITION Facts, information and articles about the Lewis And Clark Expedition, an event ofWestward Expansion from the Wild West LEWIS AND CLARK EXPEDITION FACTS Born (Meriwether) Lewis: August 18, 1774; (William) Clark: August 1, 1770 Died: Merriweather Lewis: October 11, 1809; William Clark: September 1, 1838 Spouses: Lewis: none; Clark: Julia Hancock (1808 – 1820), Harriet Kennerly Radford (1820 – 1831) Years Of Service: Lewis: US Army (1794 – 1801), Governor of the Louisiana Territory (1807 – 1809); Clark: US Militia (1789 – 1796), Governor of the Missouri Territory (1813 – 1820) Ranks:Lewis: Captain; Clark: Lieutenant Commands:Co-commanders of the Corps of Discovery Achievements:Lewis: Persona Secretary to Pres. Jefferson; Clark: Appointed Brigadier General of the Militia and Superintendent of Indian Affairs. LEWIS AND CLARK ARTICLES Lewis And Clark Expedition summary: The United States purchased Louisiana from France in 1803. The huge part of the land west of the Mississippi River was completely unknown to Americans and needed to be examined first before it could be settled. President Jefferson decided to send an exploratory expedition west so he appointed his own private secretary, Meriwether Lewis as a Commander in charge of the expedition and finding appropriate guides for it. Lewis invited his former superior officer from the Army, William Clark, to be his Co-commander. The Lewis And Clark Expedition Begins Their mission was to explore the unknown territory, establish trade with the Natives and affirm the sovereignty of the United States in the region. One of their goals was to find a waterway from the US to the Pacific Ocean. Lewis and Clark commanded the Corps of Discovery which consisted of 33 people, including one Indian woman and one slave. Sacagawea Serves As A Guide The expedition lasted from May 1804 until September 1806. They failed to find a waterway from the Mississippi to the Pacific, but succeeded in documenting more than 100 new animals and 178 plants, as well as providing 140 maps of the region. The expedition was so marked in history that the story of the explorers was made into many films and many books have been written about them. Sacagawea was a Native American who guided their mission because she knew the native land far better than the European travelers. The travelers, Sacagawea and often her husband are depicted in many different ways in paintings, carvings, and in media. Chisholm Trail From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 1. The Chisholm Trail was a trail used in the post-Civil Warera to drive cattle overland, from ranches in Texas to Kansasrailheads. The portion of the trail marked by Jesse Chisholmwent from his southern trading post near the Red River, to his northern trading post near Kansas City, Kansas. 2. Texas ranchers using the Chisholm Trail started on the route from either the Rio Grande or San Antonio and went to the railhead of the Kansas Pacific Railway in Abilene, Kansas, where the cattle would be sold and shipped eastward 3. The trail is named for Jesse Chisholm, who had built several trading posts in what was then Indian Territory and is now central Oklahoma, before the American Civil War. Immediately after the war, he and the Lenape Black Beaver collected stray Texas cattle and drove them to railheads over the Chisholm Trail,[citation needed] shipping them to the East to feed citizens, where beef commanded much higher prices than in the West. Mormon Trail: The history of the Mormon Trail cannot be understood without an awareness of the Mormon religion itself. The great Mormon migration of 1846-1847 was but one step in the Mormons' quest for religious freedom and growth. The Mormon religion, later known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was founded by Joseph Smith on April 6, 1830 in Fayette, New York. Smith experienced visions as a teenager and would later be regarded as a prophet by the Mormons. In 1827, he claimed that an angel showed him buried gold plates which he then transcribed into The Book of Mormon. All who subscribed to the beliefs of this text became known as Mormons. Membership grew rapidly, but not all were enthused about Smith's new religion. Persecution of the Mormons led to subsequent moves westward for the church, first to Ohio, then to Missouri and then to Nauvoo, Illinois. Smith envisioned a permanent settlement in Nauvoo. But both the Mormons' time in Nauvoo and Smith's life were to be short-lived. From 1839 until 1846, the Mormon church was headquartered in Nauvoo where church members were able to prosper and practice their religion peacefully. But before long, tensions arose when many citizens began to view the Mormons with contempt. Mormon practices such as polygamy, in combination with the quick growth of the church, contributed to a growing intolerance among some Illinois citizens. Hostilities broke out and on June 27, 1844, Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were killed by an angry mob while jailed in Carthage, Illinois. Brigham Young stepped in as Smith's successor and immediately began furthering Smith's plans for a move to the Far West. By now, the Mormon population of Nauvoo neared 11,000, making it one of the largest cities in Illinois. Yet the persecution of Mormons continued. In one month alone in 1845, more than 200 Mormon homes and farm buildings were burned around Nauvoo in an attempt by foes to force out the Mormons. Possible locations for a new home for the Mormons included Oregon, California and Texas. But with Smith's acquisition of John Fremont's map and report of the West in 1844, the Salt Lake region of Utah was chosen as the Mormons' destination. Young and his devotees made plans for an exodus to this new land. By 1846 the Mormon migration had begun. TRAIL OF TEARS: At the beginning of the 1830s, nearly 125,000 Native Americans lived on millions of acres of land in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina and Florida–land their ancestors had occupied and cultivated for generations. By the end of the decade, very few natives remained anywhere in the southeastern United States. Working on behalf of white settlers who wanted to grow cotton on the Indians’ land, the federal government forced them to leave their homelands and walk thousands of miles to a specially designated “Indian territory” across the Mississippi River. This difficult and sometimes deadly journey is known as the Trail of Tears. THE “INDIAN PROBLEM” White Americans, particularly those who lived on the western frontier, often feared and resented the Native Americans they encountered: To them, American Indians seemed to be an unfamiliar, alien people who occupied land that white settlers wanted (and believed they deserved). Some officials in the early years of the American republic, such as President George Washington, believed that the best way to solve this “Indian problem” was simply to “civilize” the Native Americans. The goal of this civilization campaign was to make Native Americans as much like white Americans as possible by encouraging them convert to Christianity, learn to speak and read English, and adopt European-style economic practices such as the individual ownership of land and other property (including, in some instances in the South, African slaves). In the southeastern United States, many Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek and Cherokee people embraced these customs and became known as the “Five Civilized Tribes.” But their land, located in parts of Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, Florida and Tennessee, was valuable, and it grew to be more coveted as white settlers flooded the region. Many of these whites yearned to make their fortunes by growing cotton, and they did not care how “civilized” their native neighbors were: They wanted that land and they would do almost anything to get it. They stole livestock; burned and looted houses and towns;, and squatted on land that did not belong to them. State governments joined in this effort to drive Native Americans out of the South. Several states passed laws limiting Native American sovereignty and rights and encroaching on their territory. In a few cases, such as Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the U.S. Supreme Court objected to these practices and affirmed that native nations were sovereign nations “in which the laws of Georgia [and other states] can have no force.” Even so, the maltreatment continued. As President Andrew Jackson noted in 1832, if no one intended to enforce the Supreme Court’s rulings (which he certainly did not), then the decisions would “[fall]…still born.” Southern states were determined to take ownership of Indian lands and would go to great lengths to secure this territory. INDIAN REMOVAL Andrew Jackson had long been an advocate of what he called “Indian removal.” As an Army general, he had spent years leading brutal campaigns against the Creeks in Georgia and Alabama and the Seminoles in Florida– campaigns that resulted in the transfer of hundreds of thousands of acres of land from Indian nations to white farmers. As president, he continued this crusade. In 1830, he signed the Indian Removal Act, which gave the federal government the power to exchange Native-held land in the cotton kingdom east of the Mississippi for land to the west, in the “Indian colonization zone” that the United States had acquired as part of the Louisiana Purchase. (This “Indian territory” was located in present-day Oklahoma.) The law required the government to negotiate removal treaties fairly, voluntarily and peacefully: It did not permit the president or anyone else to coerce Native nations into giving up their land. However, President Jackson and his government frequently ignored the letter of the law and forced Native Americans to vacate lands they had lived on for generations. In the winter of 1831, under threat of invasion by the U.S. Army, the Choctaw became the first nation to be expelled from its land altogether. They made the journey to Indian territory on foot (some “bound in chains and marched double file,” one historian writes) and without any food, supplies or other help from the government. Thousands of people died along the way. It was, one Choctaw leader told an Alabama newspaper, a “trail of tears and death.” THE TRAIL OF TEARS The Indian-removal process continued. In 1836, the federal government drove the Creeks from their land for the last time: 3,500 of the 15,000 Creeks who set out for Oklahoma did not survive the trip. The Cherokee people were divided: What was the best way to handle the government’s determination to get its hands on their territory? Some wanted to stay and fight. Others thought it was more pragmatic to agree to leave in exchange for money and other concessions. In 1835, a few self-appointed representatives of the Cherokee nation negotiated the Treaty of New Echota, which traded all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi for $5 million, relocation assistance and compensation for lost property. To the federal government, the treaty was a done deal, but many of the Cherokee felt betrayed: After all, the negotiators did not represent the tribal government or anyone else. “The instrument in question is not the act of our nation,” wrote the nation’s principal chief, John Ross, in a letter to the U.S. Senate protesting the treaty. “We are not parties to its covenants; it has not received the sanction of our people.” Nearly 16,000 Cherokees signed Ross’s petition, but Congress approved the treaty anyway. By 1838, only about 2,000 Cherokees had left their Georgia homeland for Indian territory. President Martin Van Buren sent General Winfield Scott and 7,000 soldiers to expedite the removal process. Scott and his troops forced the Cherokee into stockades at bayonet point while whites looted their homes and belongings. Then, they marched the Indians more than 1,200 miles to Indian territory. Whooping cough, typhus, dysentery, cholera and starvation were epidemic along the way, and historians estimate that more than 5,000 Cherokee died as a result of the journey. By 1840, tens of thousands of Native Americans had been driven off of their land in the southeastern states and forced to move across the Mississippi to Indian territory. The federal government promised that their new land would remain unmolested forever, but as the line of white settlement pushed westward, “Indian country” shrank and shrank. In 1907, Oklahoma became a state and Indian territory was gone for good. OREGON TRAIL Facts, information and articles about The Oregon Trail, a part of Westward Expansionfrom the Wild West Oregon Trail summary: The 2,200-mile east-west trail served as a critical transportation route for emigrants traveling from Missouri to Oregon and other points west during the mid-1800s. Travelers were inspired by dreams of gold and rich farmlands, but they were also motivated by difficult economic times in the east and the diseases like yellow fever and malaria that were decimating the Midwest around 1837. Fur Trappers Lay Down The Oregon Trail From about 1811-1840 the Oregon Trail was laid down by traders and fur trappers. It could only be traveled by horseback or on foot. By the year 1836, the first of the migrant train of wagons was put together. It started in Independence, Missouri and traveled a cleared trail that reached to Fort Hall, Idaho. Work was done to clear more and more of the trail stretching farther West and it eventually reached Willamette Valley, Oregon. Improvements on the trail in the form of better roads, ferries, bridges and ‘cutouts’ made the trip both safer and faster each year. There were several starting points in Nebraska Territory, Iowa and Missouri. These met along the lower part of Plate River Valley which was located near Fort Kearny. The many offshoots of the trail and the main trail itself were used by an estimated 350,000 settlers from the 1830s through 1869. When the first railroad was completed, allowing faster and more convenient travel, use of the trail quickly declined. Santa Fe Trail Edit This Page United States > Migration > Trails and Roads > Santa Fe Trail The Santa Fe Trail was an overland international trade route, military road, and pioneer migration trail in central North America between the United States and Mexico from 1821 to 1880. The Santa Fe Trail went from Missouri through Kansas, Colorado, or sometimes Oklahoma to New Mex Historical Background Shortly after Mexican independence from Spain in 1821, William Bicknell, a merchant-trader opened the Santa Fe Trail as a lucrative trade route from Franklin, Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico. During most of its history the trail was used to carry pack-trains or wagon loads of trade goods between Missouri and New Mexico. In 1846 at the start of the Mexican War the United States Army used the Santa Fe Trail to invade and later supply New Mexico. At the end of the war Mexico ceded territory that would become California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico to the United States. Some American forty-niners used the Santa Fe Trail on the way to the California gold fields. Before long, ox teams pulling wagons began to carry more and morepioneers from the expanding United States into New Mexico and the western states. Eventually, in 1880, the old wagon trail was replaced by the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway which roughly followed the Santa Fe Trail Mountain Route from Kansas City into Colorado and New Mexico.[1] Part of the reason the Santa Fe Trail was a success was because it linked the United States to two other significant trade routes, the Camino Real, and the Old Spanish Trail, all forming a hub in Santa Fe. Since 1598 the Camino Real had been used to carry settlers and goods from Mexico City and Chihuahua to Santa Fe.[2] When the Santa Fe Trail opened these Mexican goods could be traded for goods from the United States. In 1829-1830 the Old Spanish Trail also was opened connecting Los Angeles to Santa Fe making even more merchandise available for trade.[3] Settlers followed trails because forests, mountains, rivers, lakes, or deserts blocked other routes. If an ancestor settled near a trail, you may be able to trace their place of origin back to another place along the trail. Vernon, Joseph S. Along the old trail : a history of the old and a story of the new Santa Fe Trail, online through FamilySearch Catalog. Route During much of its early history, the only permanant white settlement on the Santa Fe Trail wasBent's Old Fort in Colorado. Many of the following places were built later in trail history, or after the coming of the nearby Santa Fe Railway. From east to west some of the more prominent places along or near the Santa Fe Trail included: Franklin, Missouri Independence, Missouri Council Grove, Kansas Fort Larned, Kansas Fort Dodge (Dodge City), Kansas Lakin, Kansas Cimarron Route (60 miles shorter but drier and less-dependable water and forage for livestock) Boise, Oklahoma Clayton, New Mexico Mountain Route (60 miles longer but wetter and more-dependable water and forage for livestock) Bent's Old Fort near La Junta, Colorado Raton Pass, New Mexico Trails rejoin near: Fort Union, New Mexico Las Vegas, New Mexico Santa Fe, New Mexico Settlers American pioneer settlers who followed the Santa Fe Trail to Colorado, or northern New Mexico would appear in land records, censuses, and possibly county histories. Few appear in lists as the earliest settlers because the Spanish speaking pioneers from old Mexico via the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro preceded them by many years. American settlers who travelled the Santa Fe Trail most likely would have come from Kansas,Missouri, Iowa, Arkansas,Illinois, Kentucky, or Tennessee.